Day 6 – First day in the field for “Team 2,” which consists of Kenny, Darin, and Erik from Reid Middleton, joined by Erica Fischer from Oregon State University and Brian Knight from WRK Engineers.

We knew that Mexico City is one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of 20+ million in the metropolitan area. However, it wasn’t until we flew into the expansive City that we began to grasp its scale, with dense urbanization extending into the horizon between the nearby mountain ranges. This wasn’t always habitable land; when the Aztecs founded the City (originally named Tenochtitlan) in 1325, it was on an island in Lake Texcoco, which filled the valley. Over the following centuries, generations of civil engineers designed drainage systems and ground improvements that allowed the modern City to occupy the entire lakebed.

Bottom: Aerial Photo of the Expansive Mexico City

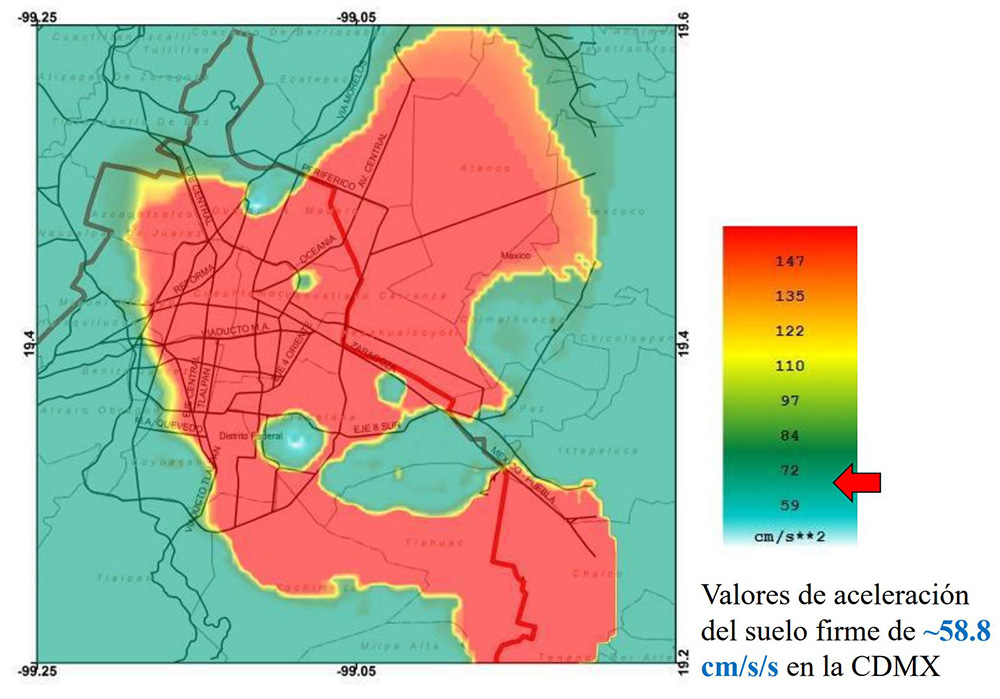

Our day began early at a meeting with a representative of Kinemetrics, our partner that provides the hardware and software technology as part of our REAP/SMS post-earthquake response and business continuity tools. We learned that there are numerous buildings in the City that have been instrumented with seismic sensors, as well as five seismic stations that measure the ground motion throughout the City. As depicted on the right, the peak acceleration is approximately 20% of gravity in the part of the City on the lakebed (meaning that if you weigh 100 pounds, it would feel like 20 pounds pushing on you sideways).

We then joined Team 1 on a field trip to Puebla, a comparatively small town of 1.5-million residents approximately 2.5 hours southeast of Mexico City. We selected this location because it is approximately 120-kilometers closer to the epicenter of the September 19th M7.1 event than Mexico City, and therefore we expected the damage in this area to be significantly worse.

Our first stop was the San Alejandro Hospital, which is operated by the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS). We had read a news article that this 41-year-old, 641-bed, 300,000 SF facility had suffered significant damage that required it to be demolished. This is a big deal as it is the largest hospital serving the Puebla community and is a critical facility, providing essential healthcare services after the earthquake. We observed damage to some of the hospital’s masonry infill wall façades. We also learned that the hospital suffered nonstructural damage that caused it to become inoperable, illustrated by the facility team removing medical equipment to an offsite location. However, based on our discussions, we understand that the plan is to repair the hospital, contrary to the media reports. Nevertheless, this hospital falls in line with lessons learned from events in Chile, China, the U.S., et al. that hospitals should to be designed to higher level of seismic performance to allow them to be immediately occupied after earthquakes. This includes structural strength/ductility, limiting building drift/movement, properly bracing nonstructural systems, and implementing technology and earthquake preparedness tools that allow for continued hospital operations after the event.

We then split into two teams and explored Puebla’s quaint city center, which is mostly comprised of 1-2 story buildings constructed of either unreinforced masonry (URM) or confined masonry (concrete frame with masonry infill walls). To our surprise, we observed minimal damage in Puebla considering the significant seismically vulnerability of these buildings. In contrast, several hundred buildings in Mexico City with more engineering suffered significant damage and catastrophic collapse (described in previous and subsequent blog posts). How could that be?

Reviewing the seismic records in the Puebla region, we found that the ground motions were less than half of those in Mexico City even though Mexico City was farther from the epicenter. In Mexico City, the localized ground motion amplifications were higher as a result of the lakebed on which the City was constructed. We knew this concept cerebrally, but by observing the contrast between Puebla and Mexico City, this abstract concept became concrete, so to speak.

Stay tuned for daily updates from our team… and if you have questions about our efforts, please comment below and we will respond with an answer.