- How did JA Brennan get started designing waterfront parks? What was the motivation?

I was really most interested in waterfront design because I am active with all kinds of water recreation. That is my personal passion for my free time; boating, fishing, swimming, kayaking, canoeing, paddle boarding, and water skiing. So, when I was in school at the University of Washington (UW), I really started to see it as a career interest of mine as well. I was also interested in habitat restoration and protecting the environment, so I got involved in salmon habitat restoration, and I did my senior project on a small fish passage project in Bellevue. Also, I was doing design-build while in college on some waterfront residential properties that included some shoreline erosion control using natural beach approaches way back in the ‘80s.

- How long have you been designing waterfront parks and how many has your firm designed?

We really started in Taiwan doing waterfront work on rivers, the ocean, and estuaries. I probably did 40 or 50 projects traveling from Seattle. Additionally, I have probably done 50 or so waterfront projects In Washington and other western states. As for my firm, I started working at Lee & Associates in 1985 then became office manager in Seattle for 15-20 years, then had the opportunity to buy the company and changed the name to JA Brennan Associates. So in essence, I have worked at the same company all but one year of my career. Joe Lee was a fantastic mentor and friend and we still work together on the occasional project.

- How has waterfront park design changed over the years?

When I first started doing the work, I was always pushing for ecological design along waterfront in a more natural approach instead of rip-rapping the shoreline. When I first began, my ideas were always seen as fringe, but over the years my approach has become much more popular. Today’s regulatory environment is requiring a softer approach to waterfront design, looking for that balance between recreational use and ecological value along the shore.

- What’s the most challenging part of designing these facilities?

Since waterfront property is really limited, there is an intense amount of interest in the shoreline areas, and for good reason as this property is really important to the community. These sites have a lot of competing interests, and the most challenging part is trying to find a way to achieve balance in the design. Ideally, coming up with multi-beneficial designs where you can overlay a recreational function with an ecological function, for instance, plus sometimes there is a working waterfront aspect; finding ways to layer multi-beneficial uses at the waterfront. Given all the pressure in that environment, I think it is really important to look for creative ideas to do this, while building consensus with multiple stakeholders, as well as the regulatory environment.

- What do you enjoy most about designing waterfront parks?

I think that firstly, it is the imaginative process where you really think about that edge between water and land and how to articulate that. As you develop the design, and you are thinking of all these uses, and you’re thinking about the character of the shoreline…that imaginative process is what I enjoy most. You kind of picture what it is going to look like in your mind’s eye as you look at a drawing or site.

Secondly, because of all the complexity, it is the collaborative approach where you learn from other people. Look at your crew at Reid Middleton, learning from Shannon, Hugh, and Jon, it is just amazing to work with people who have all these specialties and pulling that all together. It is really fun.

- Tell me a bit about your a unique waterfront park project that you worked on?

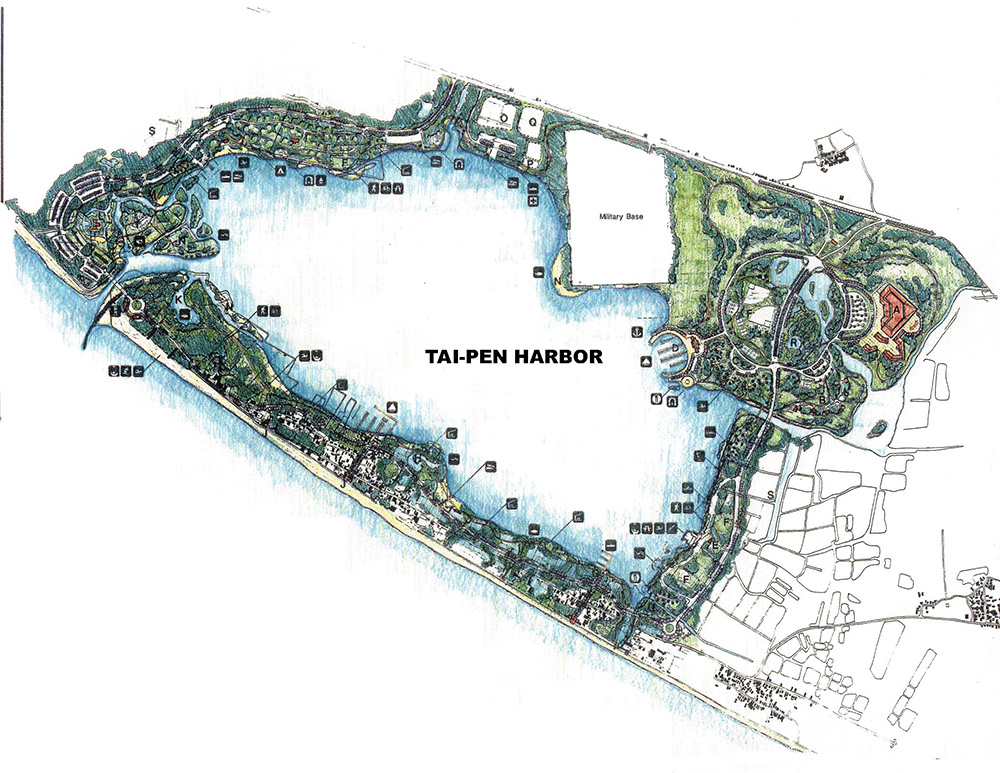

Early in my career we did a project in Taiwan, the Tai-Pen Harbor Project, and it was really fascinating because we worked on a lagoon about the size of Lake Union along the west coast of Taiwan. We had to take a lagoon that was extremely polluted, and it had a lot of shrimp, oyster and mussel farms, along with agriculture that was contributing to the water quality impacts and take that from this heavily degraded environment and turn it into a recreational amenity, developing some tourism opportunities, restoring mangrove, developing camping and marinas, and opening up beach access areas. It was an open coastal strip and spit environment, along with an inner harbor which was a more protected environment – overall an amazingly complex environment with three different villages located on the harbor.

In dealing with the contamination, we looked at a strategy to add a second channel from the ocean into the lagoon to aide in tidal flushing. There we only had about a two-foot tidal change, not nearly as much as we have here in western Washington. We pushed for source control of the pollutants, and we reclaimed the former farming space and did a lot of mangrove restoration as well as recreational improvements in those zones.

- To what extent are the actual users of the new facility included in the design process?

We try to include them, and of course our clients want to do that typically too. At Don Morse Park in Chelan, which we did with Reid Middleton, we had quite a few users; the camping community that camped there, the boating community that moored there, the sailing club, and a human-powered-boat rental concession (paddle boards, kayaks, etc.) were heavily involved, among others. Overall, there were a large number of recreational users that we brought into the mix in addition to the greater public and the community. We had seven or eight public council meetings where there was a lot of follow-through, and then we had four public meetings during the design process, and we had stakeholder meetings. We were on a first name basis with a lot of folks who were at every meeting and participated in the entire process.

- What outside influences most affect the waterfront park market sector, and new design?

The regulatory environment is a big influence. It really limits what you can and cannot do. As part of that, the desire is there to improve the ecological value of the shoreline plus there are a lot of grants and funding available to do ecologic interventions. There is so much focus on the health of Puget Sound. Scientists are now finding that stormwater impacts on salmon are lethal. In one recent study that was reported in the Seattle Times, adult Coho salmon were observed swimming in a stormwater stream, and they were dead in about two hours. There is more science coming out that is showing the negative impacts of stormwater and salmon viability. Those are the challenges; fish runs in Puget Sound are really in trouble, and there is continual decline. I think society values Puget Sound, and the salmon is an iconic species, which also triggers funding. We are working with NOAA right now in studying how to treat stormwater coming off of their facility to reduce pollutants and improve the ecology of Lake Washington.

- April is National Landscape Architecture Month. As a landscape architect, can you please share some insights into your profession and its importance in society?

We have an excellent educational system to train landscape architects, and I am passionate about the profession. As a landscape architect, we learn about topics such as human use patterns, cultural issues, understanding soil and plants, design detailing, design aesthetics and pulling all those things together to design a project or to have a role in planning. It is a great profession and an important profession to deal with some of the problems that we have.

We overlap with a lot of other professions. We study some of the same things that architects and engineers study. We take botany courses and so on – there is just a lot of exposure to a lot of things. It is good training in collaborative design also. It creates a scenario where we can be a great team member supporting another discipline or leading a multidisciplinary team.

We contribute to overall health. Recent studies have shown that a 15 minute walk in a natural setting does so much positive good for an individual to reduce depression, help with physical fitness, reduce heart disease, etc. We provide society with the uplifting aspect of beauty and that connection with nature.

One of the things that I always say is, “Let’s build some parks and trails and connect people to nature, and we could save a lot of money on building hospitals.”